Herschel–Bulkley fluid

The Herschel–Bulkley fluid is a generalized model of a non-Newtonian fluid, in which the strain experienced by the fluid is related to the stress in a complicated, non-linear way. Three parameters characterize this relationship: the consistency k, the flow index n, and the yield shear stress  . The consistency is a simple constant of proportionality, while the flow index measures the degree to which the fluid is shear-thinning or shear-thickening. Ordinary paint is one example of a shear-thinning fluid, while oobleck provides one realization of a shear-thickening fluid. Finally, the yield stress quantifies the amount of stress that the fluid may experience before it yields and begins to flow.

. The consistency is a simple constant of proportionality, while the flow index measures the degree to which the fluid is shear-thinning or shear-thickening. Ordinary paint is one example of a shear-thinning fluid, while oobleck provides one realization of a shear-thickening fluid. Finally, the yield stress quantifies the amount of stress that the fluid may experience before it yields and begins to flow.

This non-Newtonian fluid model was introduced by Herschel and Bulkley in 1926.[1] [2]

Contents |

Definition

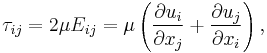

The viscous stress tensor is given, in the usual way, as a viscosity, multiplied by the rate-of-strain tensor:

where in contrast to the Newtonian fluid, the viscosity is itself a function of the strain tensor. This is constituted through the formula [3]

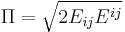

where  is the second invariant of the rate-of-strain tensor:

is the second invariant of the rate-of-strain tensor:

.

.

If n=1 and  , this model reduces to the Newtonian fluid. If

, this model reduces to the Newtonian fluid. If  the fluid is shear-thinning, while

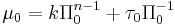

the fluid is shear-thinning, while  produces a shear-thickening fluid. The limiting viscosity

produces a shear-thickening fluid. The limiting viscosity  is chosen such that

is chosen such that  . A large limiting viscosity means that the fluid will only flow in response to a large applied force. This feature captures the Bingham-type behaviour of the fluid.

. A large limiting viscosity means that the fluid will only flow in response to a large applied force. This feature captures the Bingham-type behaviour of the fluid.

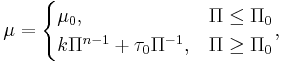

This equation is also commonly written as

where  is the shear stress,

is the shear stress,  the shear rate,

the shear rate,  the yield stress, and K and n are regarded as model factors.

the yield stress, and K and n are regarded as model factors.

Channel flow

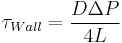

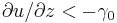

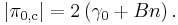

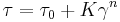

A frequently-encountered situation in experiments is pressure-driven channel flow [4] (see diagram). This situation exhibits an equilibrium in which there is flow only in the horizontal direction (along the pressure-gradient direction), and the pressure gradient and viscous effects are in balance. Then, the Navier-Stokes equations, together with the rheological model, reduce to a single equation:

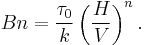

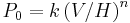

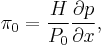

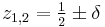

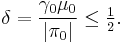

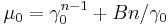

To solve this equation it is necessary to non-dimensionalize the quantities involved. The channel depth H is chosen as a length scale, the mean velocity V is taken as a velocity scale, and the pressure scale is taken to be  . This analysis introduces the non-dimensional pressure gradient

. This analysis introduces the non-dimensional pressure gradient

which is negative for flow from left to right, and the Bingham number:

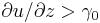

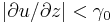

Next, the domain of the solution is broken up into three parts, valid for a negative pressure gradient:

- A region close to the bottom wall where

;

; - A region in the fluid core where

;

; - A region close to the top wall where

,

,

Solving this equation gives the velocity profile:

![u\left(z\right)=\begin{cases}

\frac{n}{n%2B1}\frac{1}{\pi_0}\left[\left(\pi_0\left(z-z_1\right)%2B\gamma_0^n\right)^{1%2B\left(1/n\right)}-\left(-\pi_0z_1%2B\gamma_0^n\right)^{1%2B\left(1/n\right)}\right],&z\in\left[0,z_1\right]\\

\frac{\pi_0}{2\mu_0}\left(z^2-z\right)%2Bk,&z\in\left[z_1,z_2\right],\\

\frac{n}{n%2B1}\frac{1}{\pi_0}\left[\left(-\pi_0\left(z-z_2\right)%2B\gamma_0^n\right)^{1%2B\left(1/n\right)}-\left(-\pi_0\left(1-z_2\right)%2B\gamma_0^n\right)^{1%2B\left(1/n\right)}\right],&z\in\left[z_2,1\right]\\

\end{cases}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/d404e07c133503206444a7b4acb51d75.png)

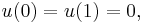

Here k is a matching constant such that  is continuous. The profile respects the no-slip conditions at the channel boundaries,

is continuous. The profile respects the no-slip conditions at the channel boundaries,

Using the same continuity arguments, it is shown that  , where

, where

Since  , for a given

, for a given  pair, there is a critical pressure gradient

pair, there is a critical pressure gradient

Apply any pressure gradient smaller in magnitude than this critical value, and the fluid will not flow; its Bingham nature is thus apparent. Any pressure gradient greater in magnitude than this critical value will result in flow. The flow associated with a shear-thickening fluid is retarded relative to that associated with a shear-thinning fluid.

Pipe flow

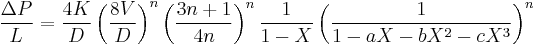

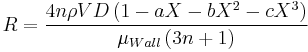

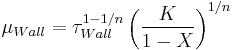

For laminar flow Chilton and Stainsby [5] provide the following equation to calculate the pressure drop. The equation requires an iterative solution to extract the pressure drop, as it is present on both sides of the equation.

- For turbulent flow the authors propose a method that requires knowledge of the wall shear stress, but do not provide a method to calculate the wall shear stress. Their procedure is expanded in Hathoot [6]

- All units are SI

Pressure drop, Pa.

Pressure drop, Pa. Pipe length, m

Pipe length, m Pipe diameter, m

Pipe diameter, m Fluid velocity,

Fluid velocity,

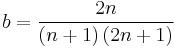

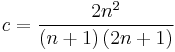

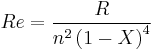

- Chilton and Stainsby state that defining the Reynolds number as

allows standard Newtonian friction factor correlations to be used.

References

- ^ Herschel, W.H.; Bulkley, R. (1926), "Konsistenzmessungen von Gummi-Benzollösungen", Kolloid Zeitschrift 39: 291–300, doi:10.1007/BF01432034

- ^ Tang, Hansong S.; Kalyon, Dilhan M. (2004), "Estimation of the parameters of Herschel–Bulkley fluid under wall slip using a combination of capillary and squeeze flow viscometers", Rheologica Acta 43 (1): 80–88, doi:10.1007/s00397-003-0322-y

- ^ K. C. Sahu, P. Valluri, P. D. M. Spelt, and O. K. Matar (2007) 'Linear instability of pressure-driven channel flow of a Newtonian and a Herschel–Bulkley fluid' Phys. Fluids 19, 122101

- ^ D. J. Acheson 'Elementary Fluid Mechanics' (1990), Oxford, p. 51

- ^ Chilton, RA and R Stainsby, 1998, "Pressure loss equations for laminar and turbulent non-Newtonian pipe flow", Journal of Hydraulic Engineering 124(5) pp. 522 ff.

- ^ Hathoot, HM, 2004, "Minimum-cost design of pipelines transporting non-Newtonian fluids", Alexandrian Engineering Journal, 43(3) 375 - 382

![\frac{\partial p}{\partial x}=\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(\mu\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right)\,\,\,

=\begin{cases}\mu_0\frac{\partial^2 u}{\partial{z}^2},&\left|\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right|<\gamma_0\\

\\\frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left[\left(k\left|\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right|^{n-1}%2B\tau_0\left|\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right|^{-1}\right)\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right],&\left|\frac{\partial u}{\partial z}\right|\geq\gamma_0\end{cases}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/953576ad21c349b96b457bf32f70696f.png)